homage to Edward Steichen

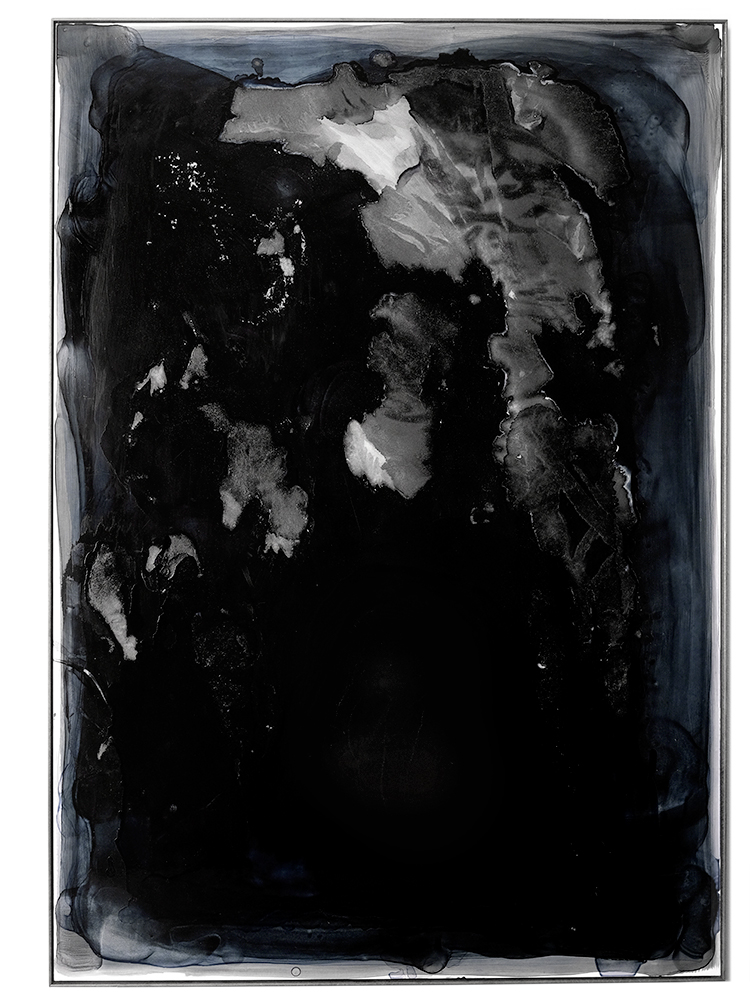

white Orchids – black paintings

white Paphiopedilum orchids (self breed over many years)

and paintings (pigments and binder on paper, 102 x 72

cm)

homage to Edward Steichen

Essay by Christoph Hessel

This is about an exhibition which forms part of fotodiskurs, a series that has steadily grown in status. As the title suggests, fotodiskurs aims to promote ‘discourse’ between photography and other visual media – sculpture, painting, graphics, drawing – and to this end also invites visitors to enter into discussion with the artists while the exhibitions are on. The fact that the series has been awarded ‘organic certification’ this time may be down to the spirit of the times.

Though in this particular case, it is unlikely to be possible because, as most observers will know, the famous American photographer Edward Steichen died a long time ago. Visitors will therefore have to make do with Christof Rehm, who is primarily (but by no means only) a photographer and is paying homage to Steichen here rather than exhibiting Steichen’s work. Upon entering the small, intimate studio, in which a red sofa (in contrast to the eponymous ‘Blue Couch’ of the interview series on Bayern 1) invites you to linger, you will be surprised not to see a single photograph – neither by Steichen nor by Rehm. The only feature reminiscent of the medium is the black-and-white colour scheme of the… let’s just call it an ‘installation’. For me, an installation is essentially a picture whose details are spread out in a real space, which usually means greater storage problems for the artist, but makes it easier to create the picture, as there is no need to represent everything – form, content, motif, meaning – on a single two-dimensional surface. The difference between a 2D image and a 3D creation is therefore not as great as avant-garde art connoisseurs (“Yuck! Painting!”) often claim (NB: Not up for ‘discourse’!).

On display are medium-format, deep black lacquer paintings. These have been coated with many layers of black pigments dissolved in a secret binding agent, one on top of the other, just enough to leave an irregular white border. In front of and alongside these paintings stand moulded porcelain vessels containing white orchids in varying shades of whiteness, all artfully arranged. The black lacquer surfaces are partly glossy, partly opaque, sometimes thicker when the paint has been poured, sometimes thinner when applied with a brush, and sometimes a glaze of colour still shines through as a residue. One could say that the inspiration comes from the North American style of reduced colour field painting as exemplified by Rothko’s later works (the black colour cushions smoothed out, no longer so cloudy, a horizon drawn in as in Sugimoto’s later sea photographs, colour-symbolic proximity to death for autobiographical reasons), by Ad Reinhard (“Art is art and everything else is everything else”), by Frank Stella’s very early works perhaps – still without ‘pot-holder minimalism’ (with a nod to Malevich’s Suprematist arrogance); after all, Richter remained stuck in the complementary grey, at least the size of a colour field wall, and there were far too many other epigones such as Klaus Umbach, who drew a black border around his stretcher frame and thus turned the picture into a wall object. Rehm emphasises the painted character with his white edges and steel frames. Of course, not all black is the same. You could write a whole book about it; indeed, others have already done so. For this reason, I’ll just offer a quote from Antonin Artaud as a possible subject for discourse: “No other painter than Van Gogh could have found this truffle-like black to paint his crows, this black ‘of a rich banquet’ and at the same time the excrement-like black of a crow’s wings surprised by the fading evening light.” (Van Gogh, der Selbstmörder durch die Gesellschaft Matthes and Seitz, 1993, p.19).

On the other hand, you might feel that you’ve been transported to the Augsburg offshoot of the State Garden Show which has also just opened in Kirchheim near Munich. (It would be nice if the planners there hadn’t laid out the site to look just like an XXL garden centre!) But no, you are a visitor here at fotodiskurs at the Berghof, attending James McNeill Whistler’s Monday Talks! And since it was likewise all about ‘discourse’ in Paris more than130 years ago, we can no longer avoid airing a few more profound thoughts.

There is ample anecdotal evidence in relevant publications that Whistler’s home was a highly aesthetic space. There wasn’t a single thing that didn’t have its aesthetically designated place in a suitable arrangement with other items selected according to aesthetic criteria. Oranges, for example, were only allowed to be displayed in azure blue glass bowls. And there is a similar look to the small fotodiskurs at the Berghof. The white orchids harmonise with the black lacquer paintings to such an extent that the viewer simply loses the desire to discuss whether such aesthetics are still appropriate today or whether they are no longer art. This is already the sort of rather superfluous ‘shithouse discussion’ (to put it crudely) which every second-rate academy graduate likes to engage in until they leave the studio sponsorship programme in order to make themselves important. Lichtwark once stated that Germans can only see with their ears, and Roger Fry, his English counterpart, said that the English are completely blind, as they always look for a moral in everything and reject anything in which they are unable to immediately discover their own(!) deeper meaning. It all makes you want to sit down on the red sofa and just look around you. And there is a lot to see in this ascetically reduced black-and-white arrangement. Contemplation is at least as discredited as aesthetics these days – but that is exactly what is needed here. For this, an approach of ‘humility’ (a term that has many negative implications because of its association with Christianity and even altruism) would not go amiss. It has simply gone out of fashion to engage in anything without immediately thinking about a selfie or a social media post.

But what exactly is it that we are being drawn into here? To answer that, we come back to the American artist. He was not only a photographer and, together with Alfred Stieglitz, the owner of the eminently important Gallery 291 in New York, but also the chairman of the Delphinium Breeders’ Association. And in 1936, he exhibited magnificent specimens of this plant species at the Museum of Modern Art, not in photographs but in real life. In keeping with Hegel’s maxim that imitation of nature only leads to a pointless duplication, no matter how perfect it may be; in any direct comparison, nature is always more beautiful than its imitation. Back in 1936, there were difficulties in scheduling the exhibition, as the delphinium also blooms and withers. Rehm’s orchids, which he has been growing himself for years, are now doing the same – hopefully they will still be in bloom at the vernissage and also at the finissage. So, is the reason he arranges the black lacquer pictures in this way because he himself only ever walks around in black clothing and takes black-and-white photos? Do Rothko’s symbolic winds blow around him? In any case, the orchid is not a flower typically found in the graveyard, and I don’t imagine there is any psychological use of colour here. However, I have been very wrong with this opinion on other occasions and with other women artists, even those who do not come from England.

Which is why I now have to talk about Lautréamont. Anyone whose education extended beyond primary school will have heard about the encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on an ironing board. The fact that Lautréamont was trying to provide a definition of beauty is less well known, as the story is always immediately taken as a reference to surrealism, which did not even exist in the middle of the 19th century. According to the story, beauty is created by depriving things of their normal utility function, rendering them unusable for a useful function and thereby also taking away their commodity status in the capitalist world. Only in this way are they opened up to have a poetic content conferred on them. Where does this content come from? Why, from the other things they encounter, of course. Unfortunately, this transubstantiation often does not work, as can be seen in many examples from the brush of René Magritte. But what is being juxtaposed in the ‘Homage to Edward Steichen’? These are not objects stripped of their utilitarian character. Here, pure nature meets pure art, with both of them enhancing each other in complementary contrast.

However, there does not seem to me to be a psycho-erotic basis for this particular composition, even if Steichen may have sniffed around the first lover and later wife of gallery co-founder Stieglitz. Contrary to popular opinion, Giorgia O’Keeffe did not so much paint blossoms and flowers as kitschy soft porn, and it cannot be denied that orchids in particular can serve as obvious vaginal-phallic models. In my opinion, Rehm’s ‘homage to Steichen’ arose from the biographical similarity of being an artist and flower grower (and gallery owner). The concept of counteracting the Hegelian verdict on ‘natural beauty’ (perhaps the deeper reason for the certification as ‘organic art’) works insofar as both parts of the installation – nature and art – complement each other. The longer you look at them, the more clearly they correspond with each other in their lineatures, form complexes and also non-colours.

Julien Green (again a suitable subject for ‘discourse’) described in his fifth diary how he looks out of the window of the country house he has recently moved into at the landscape with hills and trees, the garden with flowers and bushes in front of it, and is completely enthralled by the sight. “But If I wanted to describe it now,” he writes, “I would find it a bit boring.” Just like Hegel, for whom nature lacked ‘spirit’ which could however be found in art in the form of imagination, which nature was simply incapable of mustering. How wrong he was about that! Even the most sophisticated CGI-packed action film looks pale in comparison to the mutations that nature brings into the world. This is something that flower growers have always known.

Hommage an Edward Steichen

Essay von Christoph Hessel

Es handelt sich um eine Ausstellung im Rahmen einer inzwischen schon stattlich angewachsenen „fotodiskurs“-Serie, die sich – wie der Name schon sagt – den „Diskurs“ zwischen Foto-grafie und anderen bildnerischen Medien – Bildhauerei, Malerei, Grafik, Zeichnung – zum Ziel gesetzt hat und zu diesem Zwecke während der Ausstellungen auch zu Diskussionen mit den Künstlern einlädt. Dass sie dieses mal ein Biozertifikat erhalten hat, mag dem Zeitgeist geschuldet sein.

Im vorliegenden Fall wird das schlecht möglich sein, denn wie sicher die meisten wissen, ist der berühmte amerikanische Fotograf Edward Steichen schon vor langer Zeit gestorben. Man wird also gesprächsweise mit Christof Rehm vorliebnehmen müssen, selbst – in erster Linie, aber beileibe nicht nur – Fotograf, der hier Steichen mehr huldigt als ausstellt. Wenn man in den kleinen, intimen Ausstellungsraum kommt, in welchem keine „Blaue Couch“ wie bei Bayern 1, sondern ein rotes Sofa zum Verweilen einlädt, wird man erstaunt sein, kein einziges Foto zu sehen – weder von Steichen, noch von Rehm. Das einzige, was an das Medium erinnert, ist das durchgängige Schwarz-Weiß der – nennen wir es halt „Installation“. Für mich ist eine Installation im Kern ein Bild, welches sich in seinen Details in einem realen Raum ausbreitet, was für den Künstler meist größere Lagerprobleme bedeutet, dafür eine Erleichterung in der Bildgestaltung, da er nicht alles – Form, Inhalt, Motiv, Sinn – in einer einzigen Fläche vortäuschen muss. Der Unterschied zwischen Bildfläche und Raumgestaltung ist also gar nicht so groß wie avantgardistisch aktualisierte Kunstkenner („Igitt! Malerei!“) oft zu wissen meinen (Achtung: Kein Diskurs!).

Zu sehen sind also mittelformatige, tiefschwarze Lackbilder, die zum einen mit, in geheimem Bindemittel gelösten, schwarzen Pigmenten in vielen Schichten übereinander gerade so weit eingestrichen wurden, dass ein unterschiedlich unregelmäßiger weißer Blattrand übrig bleibt; und zum anderen weiße Orchideen in gegossenen, ebenfalls unterschiedlich weißen Porzellanbechern, vor und neben den Lackbildern in Gruppen platziert. Die schwarzen Lackoberflächen sind zum Teil glänzend, zum Teil opak, mal dichter, wenn die Farbe geschüttet wurde, mal dünner, wenn nur mit dem Pinsel aufgetragen, mitunter scheint noch eine Farblasur als Resterest durch. Man könnte sagen, es handele sich um amerikanisch inspirierte, verkleinerte Farbfeldmalerei des späten Rothko (die schwarzen Farbkissen geglättet, nicht mehr so wolkig, ein Horizont eingezogen wie in den späteren Meer-Fotografien von Sugimoto, farbsymbolische Todesnähe autobiografisch bedingt), von Ad Reinhard („Kunst ist Kunst und alles andere ist alles andere“), vom ganz frühen Stella vielleicht - noch ohne Topflappenminimalismus (an Malewitschs Suprematismus-Arroganz angelehnt); Richter blieb ja im komplementären Grau hängen, immerhin farbfeldwandgroß auch der, und viel zu vielen anderen Epigonen wie Klaus Umbach, der das Schwarz um den Keilrahmen herum zog und so aus dem Bild ein Wandobjekt machte. Rehm betont mit seinen weißen Rändern – und den Stahlrahmen – den Bildcharakter. Schwarz ist natürlich nicht gleich Schwarz. Darüber könnte man ein ganzes Buch schreiben, andere haben das schon getan. Deswegen nur ein kurzes Zitat von Antonin Artaud als Diskursangebot: „Kein anderer Maler als Van Gogh hätte, um seine Krähen zu malen, dieses Trüffelschwarz finden können, dieses Schwarz „eines reichhaltigen Banketts“ und gleichzeitig exkrementähnliche Schwarz der Krähenflügel – überrascht vom sinkenden Abendlicht.“ („Van Gogh, der Selbstmörder durch die Gesellschaft“ Matthes und Seitz, 1993, S.19).

Zum anderen fühlt man sich vielleicht in den Augsburger Ableger der Landesgartenschau in Kirchheim b. München, die auch gerade eröffnet hat, versetzt. Schön wär es ja für zumindest deren Planer, wenn ihre Anlage nicht nur wie ein XXL-Gartencenter wirken würde! Also Nein! Man ist hier im fotodiskurs am Berghof bei den Montagsgesprächen von James Mc Neill Whistler zu Gast! Und da es auch schon damals vor über 130 Jahren in Paris um Diskurs ging, kommen wir jetzt nicht mehr drum herum, ein paar tiefer gehende Gedanken ins Freie zu entlassen.

Es schwirrt als Anekdote in entsprechenden Veröffentlichungen herum, dass es bei Whistler zu Hause höchst ästhetisch zuging. Kein Ding, welches nicht seinen ästhetisch arrangierten Platz in einer passenden Zusammenstellung mit anderen nach ästhetischen Gesichtspunkten ausgesuchten Dingen innehatte. Orangen z.B. durften ausschließlich in azurblauen Glasschüsseln drapiert werden. Und ähnlich sieht es auch im kleinen fotodiskurs am Berg-hof aus! Die weißen Orchideen harmonieren mit den schwarzen Lackbildern in einem Maße, dass dem Betrachter schlicht die Lust vergeht, darüber zu diskursieren, ob solche Ästhetik heutzutage noch statthaft ist oder keine Kunst mehr. Das ist so schon eine ziemlich überflüssige, grob gesagt „Scheißhausdiskussion“, die jeder zweitrangige Akademieabsolvent bis zu seinem Abgang aus dem Atelierförderalter gern anstimmt, um sich wichtig zu machen. Schon Lichtwark bekundete, dass der Deutsche nur mit den Ohren sehen könne, und Roger Fry, sein englisches Pendant, meinte, dass der Engländer überhaupt völlig blind sei, da er immer nach einer Moral in allem suche und alles ablehne, wenn er nicht sofort s(!)einen tieferen Sinn entdecke. Man möchte sich also am liebsten auf das rote Sofa setzen und nur schauen. Und da gibt es in diesem asketisch reduzierten Schwarz-Weiß-Arrangement viel zu sehen. Kontemplation ist heutzutage ja mindestens so verrufen wie „Ästhetik“ – aber genau das braucht es hier. Und dafür wäre eine Haltung gar nicht so übel, die mit dem Begriff „Demut“ mindestens ebenso viele negative, weil christliche, wenn nicht sogar christlich-soziale Implikationen hat. Es ist eben aus der Mode, sich auf andere Dinge einzulassen, ohne gleich an ein Selfie zu denken oder einen Post.

Aber auf was sich denn eigentlich genau einlassen? Um das zu beantworten, kommen wir wieder auf den Amerikaner zu sprechen. Der war nämlich nicht nur Fotograf und mit Alfred Stieglitz zusammen Betreiber der eminent wichtigen Galerie 291 in New York, sondern auch Vorsitzender des Züchterverbandes von Rittersporn. Und Prachtexemplare dieser Gattung stellte er 1936 im Museum of Modern Art aus, nicht fotografiert, sondern real. Ganz gemäß der Hegel´schen Erkenntnis, dass Nachahmung der Natur nur zu einer blödsinnigen Verdoppelung führt und sei sie noch so perfekt; im direkten Vergleich sei die Natur allemal schöner als ihre Nachahmung. Schwierigkeiten gab es schon damals bei der Terminierung der Ausstellung, da auch der Rittersporn blüht und welkt. Bei Rehm tun das jetzt die Orchideen, die er selbst seit Jahren züchtet – hoffentlich blühen sie zur Vernissage und auch zur Finissage immer noch. Die schwarzen Lackbilder arrangiert er dazu, weil er selbst auch immer nur in Schwarz rumläuft und schwarz-weiße Fotos macht? Ob ihn Rothko´sche Symbolwinde umwehen? Eine Friedhofsblume ist die Orchidee jedenfalls nicht und ich imaginiere hier auch keinen psychologischen Farbgebrauch. Allerdings lag ich mit dieser Meinung bei anderen Gelegenheiten und Künstlerinnen schon sehr daneben, obwohl die nicht aus England kamen.

Deshalb muss ich jetzt auch noch auf Lautréamont zu sprechen kommen. Den Spruch von der Begegnung einer Nähmaschine und eines Regenschirms auf einem Bügelbrett wird jeder schon mal gehört haben, der eine höhere Schule als die Grundschule besucht hat. Dass Lautréamont damit eine Definition des Schönen liefern wollte, ist weniger bekannt, da der Spruch immer sofort auf den Surrealismus bezogen wird, den es Mitte des 19.Jahrhunderts noch gar nicht gab. Das Schöne entsteht demzufolge dadurch, dass Dinge ihrer normalen Gebrauchsfunktion beraubt, für eine nützliche Funktion unbrauchbar werden – damit auch ihres Warencharakters in der kapitalistischen Welt verlustig gehen - und sich nur so dafür öffnen, einen poetischen Inhalt zu bekommen. Woher? Na, von den anderen Dingen, denen sie begegnen, natürlich. Leider klappt diese Transsubstantiation häufig nicht, was man an vielen Beispielen aus dem Pinsel René Magrittes studieren kann. Was trifft sich nun aber in der „homage to Edward Steichen“? Das sind ja keine ihres Gebrauchscharakters enthobene Gegenstände. Hier trifft sich „Natur“ pur mit „Kunst“ pur, um sich gegenseitig zu steigern wie ein Komplementärkontrast.

Eine psychologisch-erotische Grundlegung dieser speziellen Zusammenstellung scheint mir hingegen nicht vorzuliegen, auch wenn Steichen vielleicht bei der erst Geliebten und späteren Gemahlin seines Kompagnons Stieglitz vorbeigerochen haben sollte. Giorgia O´Keeffe hat ja entgegen volkshochschulischer Auffassung weniger Blüten und Blumen als vielmehr kitschige Softpornos gemalt und es ist nicht zu leugnen, dass auch gerade Orchideen dafür als naheliegende vaginal-phallische Vorlagen dienen können. Die Rehm´sche Hommage an Steichen ist meines Erachtens aus der biografischen Gemeinsamkeit, Künstler und Blumenzüchter (und Galeriebetreiber) zu sein, heraus entstanden. Das Konzept, das Hegel´sche Verdikt der „Naturschönheit“ zu konterkarieren (vielleicht der tiefere Grund für das Biozertifikat „Bio-Kunst“), funktioniert insofern, als sich beide Installationsteile – Natur und Kunst- gegenseitig ergänzen. Je länger man sie betrachtet, desto deutlicher korrespondieren sie in ihren Lineaturen, Formkomplexen und auch Nicht-Farben miteinander.

Julien Green (durchaus wieder diskursfähig) beschrieb in seinem 5. Tagebuch wie er aus dem Fenster seines frisch bezogenen Landhauses auf die Landschaft mit Hügeln und Bäumen blickt, davor der Garten mit Blumen und Büschen, und ganz begeistert ist von diesem Anblick. Aber. Wenn ich das jetzt beschreiben wollte, schreibt er, dann finde ich das doch etwas langweilig. Wie auch schon Hegel, dem bei der Natur der „Geist“ fehlte, bei der Kunst in Gestalt der Phantasie, die die Natur nun einfach nicht aufbringen könne. Wenn er sich da mal nicht geirrt hat! Was die Natur so alles an Mutationen in die Welt setzt, dagegen schaut auch der gekonntest digital ausgetrickste Äktschnfilm matt aus. Ein Blumenzüchter weiß das schon immer.

contact

Christof RehmPavillon am Berghof

Bergstrasse 12

86199 Augsburg

mail@christof-rehm.de

www.christof-rehm.de